Part Writing is an example of strict composition. By strict, I mean that we are composing music with exact standards and stylistic expectations. This allows us to zero in on a few specific musical traits and really work on learning their possible applications.

Basic Principles

Combining Melodies Creates Harmony

Although we spend a lot of time talking about chords and harmony, classical music in most periods is actually lots of melodies put together at the same time. Like we can think of hymns as a bunch of chords stapled together to form the music, but we actually use groups of people singing four melodies at the same time to create this beautiful euphony. So we want to focus on the melodic nature of each voice part as well as the resulting chord that we place a Roman numeral under.

Voice Independence

Since we are thinking of every part as a melody, we want to make sure we allow them to be separate from each other. This is the idea of voice independence. We want to avoid any combination or succession that fuses multiple voices into one thing. Here’s an experiment to illustrate this concept.

- Find a friend and/or a piano.

- Play an easy little melody of all half notes. This could just be a scale.

- Now play another melody of all half notes at the same time in the same key.

- Notice how each harmonic interval sounds, and how the melodies interact when they go in the same direction vs. going in opposite directions. Does it always sound like two things or does it sometimes sound like one thing?

- Now play the same melody but in octaves. Does this sound like two things or one thing?

- Now play the same melody in parallel fifths. Does this sound like two things or one thing?

I won’t spoil your answer, but if you carry this out, you will hear why common-practice music often avoids parallel octaves and parallel fifths. We want all four voices in our part writing to be independent.

Smooth Voice Leading

Another important idea is smoothness. In general, we want to move each voice by the smallest amount possible as we change chords. If chords have common tones, hold the same note over in the same voice. We prefer steps and 3rds to larger leaps. 4ths and 5ths are common in the lowest voice.

Of course, there will be times we want and have large leaps, especially in the top and bottom voices. But these are expressive moments, places that achieve musical interest because they step outside our smooth expectations.

Independence vs. Smoothness

You need to know that there are circumstances when our ideals for independent voices that all move smoothly do not align. An example is writing IV–V. If we move each note in IV to the closest note inV, we end up moving each voice up by step. This awesome smoothness creates all possible parallels that destroy voice independence. In this instance, we prefer to move only the root up by step, and everyone else moves down to the closest note. This is less smooth, but the voices are independent.

Style Guidelines

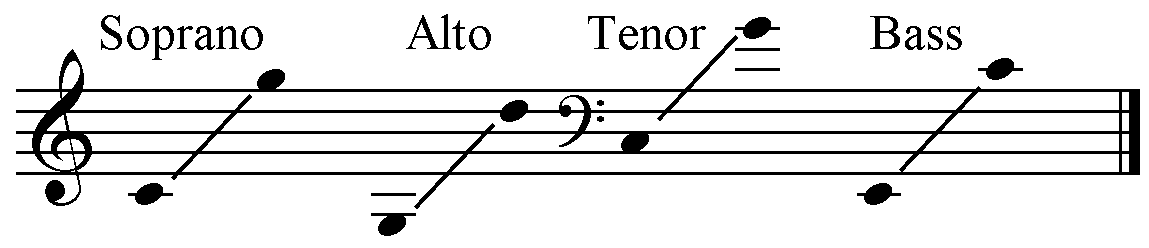

As I said above, our part writing is in the style of four-part hymns. We are writing for choir: soprano, alto, tenor, and bass (SATB, I will often use S for soprano, and so on as we move forward). And our choir is not made up of virtuosos. They have small vocal ranges to keep everything sounding lovely.

Also, we are copying musical ideals that are, in some corners, 125 years out of date. I love the sound of parallel fifths (power chords!); so did Debussy, who died in 1918. We are used to the sounds of natural minor as a way of organizing music (so was Debussy!). But in Europe in the 18th and 19th centuries, minor includes leading-tones. So you need to remember accidentals for Ti. A minor v chord going to i sounds normal to me, but it is unstylistic when we are trying to copy Mozart or Bach.